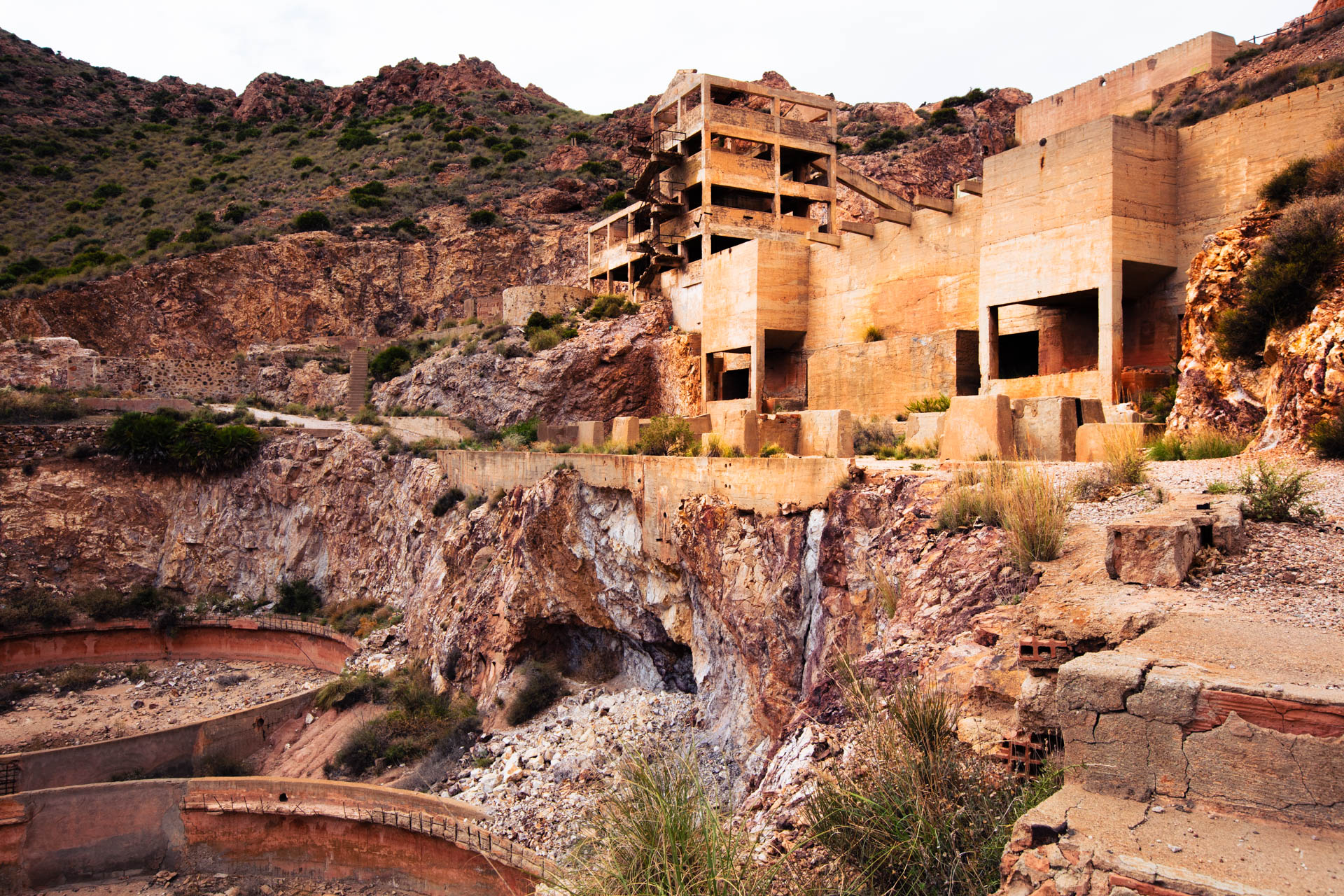

The Gold Mines of Rodalquilar

I had no idea, as recently as two weeks ago that there had ever been a goldrush in Andalucia. A visit to the gold mines of Rodalquilar put me right on that score, a fascinating story of greed, incompetence and ultimately, restoration in the Cabo de Gata.

This is not my usual photowalk, I’m usually drawn to the mountains and forests of the Sierra Nevada, but I am fascinated by abandoned buildings, especially those with a brutalist architectural bent and this was too good an opportunity to miss.

Rodalquilar is a small town slightly inland from the beaches and bars of the Cabo de Gata coastline. It is roughly in the centre of the crater or caldera of an extinct volcano. Home to a thriving artistic community and a large botanical garden, Rodalquilar was also the site of a frantic riches-to-rags story that consumed private companies, state-run enterprises and hundreds of itinerant workers whose ruined cottages are still standing, abandoned and graffitied, covering an area way larger than the remaining village.

But first, let’s have a quick historical recap, the area has been mined for centuries, since Roman times in fact, for zinc, lead and silver, as volcanic activity taking place millions of years ago, produced a layer of mineral rich quartz comparatively close to the surface.

The Story of the Gold Mines of Rodalquilar

In fact, so successful was the extraction of minerals in the area that fortifications were built on the coast to protect it. Notably Bateria de San Roman and Torre de los Alumbres.

Mining gradually petered out until 1864 when a prospector discovered gold in the crater of an extinct volcano. By the end of the year the word was out and dozens of small independent mining groups opened up shop. Extracting the gold from the rock was not simple, unlike the American west where gold nuggets could be filtered out of the soil manually, this gold required a toxic chemical process using mercury to leach the gold from the manually powdered quartz.

Miners in those days carried the ore to the surface from mines dug deep into the mountainside, in sacks on their backs, breathing in the dust caused by breaking the rocks with pick axes. Hard work in the blazing heat of summer with only respiratory disease (silicosis) waiting at the end of it.

In 1915 more gold was discovered in the “Maria Josefa” mine and newly available technology enabled a gold extraction plant to be built at Cortijo El Estanquillo nearby. This plant also served the mines of “Las Niñas”, “Ronda” and “Consulta”. In 1916, approximately 2,500 tonnes of ore was mined, producing a mere 50kg of gold. It could not go on, but of course, it did. Just as old technology ran out of momentum, new technology fulled false hopes of incredible wealth and success.

In 1925 two specially formed companies, Rodalquilar Gold Mines Company and the Exploitation of Rodalquilar Gold Mines Company entered the fray. They set up a state-of-the-art amalgamation plant treating 20 tonnes of ore a day. They lasted one year, and the mines were silent for a further three.

In 1929, the British arrived on the scene, oblivious to the dismal history, an Anglo Spanish company called Minas de Rodalquilar had a go using explosives and compressed air drills to get at the ore in the hills. Rails were laid in the main mineshafts and the miners, instead of humping sacks of ore to the surface on their backs, pushed wagons of ore along the trails to the surface. They also used a new and doubly toxic cyanide based extraction process at a specially constructed extraction plant known as Dorr Mill.

Against all the odds, this company was moderately successful until the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, when the mines were seized and taken over by the sindicalists (Trade Unions). Without further investment, production quickly fell to zero.

In 1946 the mines were nationalized and run by the state. Improved technology replaced the air drills with pneumatic, water-powered drills, which happily proved to be more efficient and dramatically reduced the incidence of silicosis in the miners. Miraculously, under Franco’s regime and with new technology, the mine became viable for the first time – until the gold ran out. Production ceased in 1966.

One last roll of the dice occurred in 1989 when somebody came up with the bright idea of open cast mining. Bankrupt within twelve months.

Today the abandoned cottages and mineworks make for an excellent photowalk. You’ll see the miner’s dwellings off the road on the way in to the village.

You can drive to the museum, and take the “Devil’s Staircase” (so called because of the hellish conditions awaiting the hapless miners at the top) to the Denver Process Plant and wander about the ruins. The entrances to the mines themselves are sealed but the brutalist architecture of the process plant is amazing.

Alternatively, you can drive to the top level and walk about 50 metres to the processing plant. Further up the hill and you can see more abandoned villages and disused mineworks on the other side.

From the photographic perspective, the abandoned buildings and machinery are a gift. I mostly used a 16-35mm lens to give me a wide angle of view and make the already imposing architecture all the more imposing. The cottages were shot at around 35mm with a 24-70mm lens and the ‘works’ around 16mm.

If you visit the Cabo de Gato, this site is well worth a visit.

I did mention restoration at the top of the article. In the village, there is an extensive botanical garden, for which the area is becoming well known. For me, no amount of botanical garden will top the story of Spain’s only gold rush and the mining works that literally overshadow the village.

Subscribe…

I’ll keep you in the loop with regular monthly updates on Workshops, Courses, Guides & Reviews.

Sign up here and get special prices on all courses and photowalks in 2024